Originally published in Ultrarunning Magazine, September 2002. Reprinted with permission.

Running in hot weather can pose many dangers to ultrarunners. Although most runners are aware of the dangers of running for prolonged distances in hot and humid weather, many are also inadequately prepared for the intense stress placed on the body during these hot weather runs.

This past July, I participated in the 25th anniversary of the Badwater Ultramarathon, a 135-mile trek from the lowest place in the continental United States (Badwater Basin), through Death Valley National Park, and to the foot of Mount Whitney, the Whitney Portals, at an altitude of 8,360 feet (2,548 meters). The run was held in the middle of one of the most severe heat waves southern California has ever seen. In preparation for the run, I made sure my crew was aware of the signs and symptoms of heat illness, as well as how to treat me should problems occur. Here are some of the dangers of ultrarunning in the heat, and preventative measures that can be taken to avoid potential problems.

The heat index is the apparent temperature felt by the body due to the combined effects of actual temperature and humidity. Most people understand that as the air temperature goes up, so does the heat index, but humidity also plays a role. As the humidity rises, the body is unable to efficiently evaporate the sweat it produces. Therefore, the perceived temperature is much higher than the actual air temperature. The loss of cooling efficiency thus makes exercise extremely dangerous.

Although it is convenient to use a single number to describe the apparent temperature your body feels, keep in mind that heat and humidity affect everybody differently. Several assumptions are made to calculate the heat index measurements in the table below. Specifically, the heat index assumes the body to be:

Changing any of these factors can either increase or decrease the heat index from those shown in the table. Be aware that heat index values of over 100 significantly increase your risk of heat-related illness.

Air Temperature (degrees Fahrenheit) |

|||||||||||

| Relative Humidity |

70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 110 | 115 | 120 |

Heat Index |

|||||||||||

| 0% | 64 | 68 | 73 | 78 | 83 | 87 | 91 | 95 | 99 | 103 | 107 |

| 10% | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 111 | 116 |

| 20% | 66 | 72 | 77 | 82 | 87 | 93 | 99 | 105 | 112 | 120 | 130 |

| 30% | 67 | 73 | 78 | 84 | 90 | 96 | 104 | 113 | 123 | 135 | 148 |

| 40% | 68 | 74 | 79 | 86 | 93 | 101 | 110 | 123 | 137 | 151 | – |

| 50% | 69 | 75 | 81 | 88 | 96 | 107 | 120 | 135 | 150 | – | – |

| 60% | 70 | 76 | 82 | 90 | 100 | 114 | 132 | 149 | – | – | – |

| 70% | 70 | 77 | 85 | 93 | 106 | 124 | 144 | – | – | – | – |

| 80% | 71 | 78 | 86 | 97 | 113 | 136 | 157 | – | – | – | – |

| 90% | 71 | 79 | 88 | 102 | 122 | 150 | 170 | – | – | – | – |

| 100% | 72 | 80 | 91 | 108 | 133 | 166 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Data from the US National Weather Service | |||||||||||

There are three major heat illnessesand all of them can be exacerbated by ultra distance running and prematurely end an ultrarunner’s race. In all cases, the main reason that runners experience heat illness is dehydration. If you replace lost fluids and electrolytes and are able to train your body to process a high volume of fluid in a short period of time, you significantly decrease the risk of experiencing these race-ending medical emergencies.

Heat cramps: Exercising in hot weather can lead to muscle cramps, especially in the legs. This is usually caused by imbalances or deficiencies in your body’s electrolyte stores. A cramp is characterized by sharp, stabbing pain in the muscle and rarely works itself out on its own. On a training run earlier this year in Death Valley, many runners complained of cramps in their legs; I suffered from cramps in my diaphragm and had difficulty breathing for more than an hour! Cramps become less frequent with heat training, but for those of us unaccustomed to such extreme conditions, maintaining adequate hydration and electrolyte balance is critical to avoiding them. To eradicate cramps, you should stop running, drink fluids containing electrolytes, cool your body with wet towels, and immediately get out of the sun.

Heat exhaustion: Losing fluid and electrolytes through sweat leads to dizziness and weakness if the lost fluids are not replaced. Heat exhaustion is characterized by a moderate rise in body temperature, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, and a headache. You might also experience weakness, lack of coordination, heat cramps, heavier than usual sweating accompanied by moist and cold skin, and “goose bumps.” Your heart rate may rise and you won’t be able to run as fast due to fatigue. Many runners even those who are well trained will suffer from mild heat exhaustion after running for several hours in hot and humid conditions. If you experience the signs of heat exhaustion, stop running immediately and drink fluids containing electrolytes, cool your body with wet towels, lie down and elevate your feet a few inches above your heart, and immediately get out of the sun. Since heat exhaustion can lead to the most severe form of heat-related illness, heat stroke, seeking prompt medical attention for heat exhaustion is also highly recommended.

Heatstroke: In extreme cases heat can upset the body’s thermostat, causing body temperature to rise to105 degrees F or higher. This is a life-threatening situation that requires immediate medical attention. While it is common for untreated heat exhaustion to rapidly progress to heatstroke, heatstroke can (and does) occur without the signs of heat exhaustion being apparent. Symptoms of heatstroke include lethargy and extreme weakness, confusion and odd or bizarre behavior, disorientation and unconsciousness. Because heatstroke is a complete failure of the body’s temperature regulation system, sweating ceases and the skin becomes hot and dry. Convulsions or seizures can occur as the brain begins to shut down. Coma and death are also possible in extreme cases. Heatstroke is a medical emergency that requires immediate medical attention. Call the emergency response system immediately! Get the runner out of the sun, remove all clothing, and immediately rub their body with ice or immerse the runner in cold water.

By staying properly hydrated and recognizing the early warning signs of heat illness, as a runner you can prevent a heat-related problem from becoming a life-threatening situation. As a volunteer, recognizing these heat-related dangers may one day help you save the life of a runner who has underestimated the intensity of the surroundings.

Jay is a nationally Certified Athletic Trainer (ATC) licensed to practice in Indiana. He holds Master’s degrees in Exercise Physiology and the Basic Medical Sciences, both from Purdue, with an emphasis on tissue repair and healing. Jay works full-time as the Clinical Affairs Manager for Cook Biotech Incorporated, a medical device company in Indiana. He has completed over 60 ultramarathons, including the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning and the 2006 Badwater Ultramarathon.

Badwater finishers and ZombieRunner proprietors

Plans for the Badwater 135 Ultramarathon typically include long lists of items for the runner. What people may overlook is that the crew needs to be outfitted, too. Everyone will be out there in the same heat, needing fuel, hydration, cooling, and some rest. Planning your gear list makes all the difference to your race. Take time to think through scenarios and have backup items in case other items fail or things don’t go as expected.

Hope for the best but prepare for the worst. People who never get blisters can end up with serious foot issues during Badwater 135. Keep foot care items in a cool place. If possible, dedicate a small cooler to these types of items. Tapes can melt and become useless quickly if they get too warm.

Finally, bring along any other items that might make your journey more comfortable and enjoyable! Just remember to stay within the rules and be considerate of other people who are out there.

Running the Badwater Ultramarathon is the true test of an athlete’s endurance, training, tactics and proper body maintenance. One of the obstacles that seems to prevent many from finishing is problems with blistering. Before competing in my first Hi-Tec Badwater race in 1994, I had the privilege of Rhonda Provost teaching me foot-care techniques. (She’s the only woman to have done the double-crossing from Badwater to Whitney and back in 1995.) Since that time, I’ve taken advice from other runners as well, with the hopes that we could devise some way to prevent the inevitable blistering problems that develop during this event. When I competed the second time in 1996, I was able to finish the race with NO blisters at all by using the following techniques. My hope is that these tips will help you, the competitor, successfully travel this course in more comfort, due to sharing the techniques I have learned over the years.

I have seen and worked on feet so unbelievably blistered from this event it would make you think they have been boiled in oil. Often it has been a complete surprise to the athlete, as more often it seems many have taken it for granted that they won’t blister in Badwater because they don’t blister in other 100 milers. Please take the precautions, and maybe you can get through this event without them! Even with these measures I suggest, it’s not always the cure. In 1998 I spent significant time with Robert Thurber from Texas. By Panamint (72 miles) even with prior taping, his feet were so bad he had to be carried off the course. I tried everything to prevent this from happening to him, but his calluses were very thick, and he had blistered massively on his heels under them.

I also highly recommend the book advertised in UltraRunning Magazine, “Fixing Your Feet”, by John Vonhof. It is a very complete practical synthesis on proper foot care. He goes into a lot of specifics on every detail of foot care, and where things can be purchased. It’s just great and I believe every competitor would benefit form using it as a reference.

My booklet is specific to Badwater, therefore it might differ somewhat from the techniques that Vonhof recommends in his book.

Items for foot care box:

Preparation of Feet Prior to Competition.

File down any calluses with a pedicure file so that if a blister develops you can get to it so it can be treated. If thick calluses are allowed to remain, they are next to impossible to get underneath to fix the blister during this event. Many times it has caused an athlete to drop out. Make sure toenails are trimmed (square) and file them so no rough edges remain.

Pre-Taping:

I recommend pre-taping the night before the race so the tape has time to conform to your feet. By taping the night before, it’s one less thing to get together on race day, and if anything comes unstuck it will take less time to fix. Micropore (by 3M) seems to work well (it is like paper) and conforms to the shape of the foot. Another tape that has been helpful is Elastikon (by Johnson&Johnson). It is slightly thicker and stretchy for the heels and balls of the foot and it is breathable. I DO NOT recommend duct tape. We have found that duct tape doesn’t breathe and causes the area that has been taped to become edematous, sometimes causing worse blisters underneath the tape. It also tears the skin that has been taped when it’s removed, causing a great deal of pain. Pre-tape any areas that has blistered before, or might be a friction point. Spread Tincture of Benzoin over the area to be taped. Allow the Tincture to become tacky, then tape as flatly and neatly as possible. Cut off any wrinkles or corners of the tape. Tincture of Benzoin can be purchased at a pharmacy.

Socks:

Make sure you’ve tried your socks prior to the event. Everyone seems to have their own favorite. In recent years, runners such as Monica Scholz have had excellent results (blister-free) with Injinji toe socks (known as “Tsoks”) which feature individual toes. With regular socks, seams are sometimes a problem. Sometimes it helps to turn the seam-side out. Any sock needs to fit well, with no wrinkling. Cotton socks provide no wicking and tend to make balls (pills). Any amount of sand in a sock seems to cause blistering.

Shoes:

Make sure shoes aren’t black, they absorb too much heat. Make sure insoles are insulating. I wear very padded orthotics that also provide insulation against the heat. Consider extra cushioning but don’t try something you haven’t trained with. Anklet nylons have been used to provide the innermost layer, then ultrathin socks. Personally, I found them too slippery. They caused my feet to move around too much in the shoe, which can also cause blisters. Have an extra pair of shoes available in case your feet swell. It also helps to keep them in a zip-lock bag in the ice chest, if you have room, to keep them cool. I’ve been able to complete the race in the same pair of shoes, however.

Treating Blisters After They Develop:

Clean the area with alcohol. Drain blister by cutting a hole in it, (a small hole not a pin prick.) This prevents the blister from refilling. Place Second Skin over the blister. Try to leave skin intact over the blister. Treat the area with Tincture of Benzoin, once again, so that the tape will stick. Tape over Second Skin. Once the skin is moist from sweat, it’s harder to get the tape to stick. I use foot powder (Zsasorb) to dry the feet after the benzoin and before the taping.

Lanolin or Vaseline:

Some runners like to use these preparations to prevent blistering. I have found that they don’t work for me. The drier I can keep my feet, the better. However, if using such a preparation has worked for you and you’ve trained in the desert with it, then by all means use it!

Compeed:

I have had no success using Compeed for Badwater. Others have used it to alleviate the pain of a blister quickly. The problem seems to be that it might help at the immediate time, but trying to get it off is a nightmare. It sticks to the skin and shifts. I treated three athletes last year that were in terrible pain from Duct Tape and Compeed. They wanted to climb Whitney after the race and their feet were in such bad shape they could hardly walk. In trying to remove it, the skin over the blister and the tissue underneath often comes off. The raw flesh is very tender and susceptible to infection. You might try it as a last ditch resort, but I’ve treated some very painful feet due to it’s use.

Comments from John Vonhof, author of “Fixing Your Feet”

The number one factor is knowing what your feet need, and how to do it, before you have to do it. I have patched many feet at ultras and adventure races and have found that most racers have a fairly good knowledge base of what they should be doing. They know it’s smart to wear the right kind of socks and to have footwear that fits well. Many have also made footcare kits for their crews. I would make a rough guess and say about 30-40% are well versed in what their feet need and how to do it. The other 60-70% kind of wing it. They’ve read about footcare but somehow it falls lower on the priority list than does training, finding foods they can tolerate, the right flashlight for night running, and other choices. So they start their race and manage well for a while-until problems develop.

To have and keep healthy feet, you have to know what works for them in the sports in which you participate. You also have to know what to do when what worked no longer works. In other words, a fallback plan with the equipment to back it up and the knowledge of how to use it. Let me give some examples.

The bottom line is that if you don’t learn what works for your feet, intentionally, you will learn the hard way.

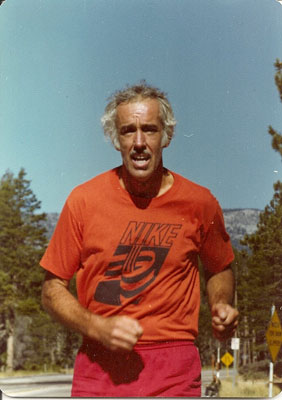

On the photo above: “That is the most inspiring photo ever taken of me: 362 days earlier I was in Wilcox Hospital, Maui. I was told: ‘Maybe, in one year, and using a walker, you might be able to take a few steps.’ 362 days later, I jogged a 100 mile loop which included some side-trails and the full circle around Lake Tahoe. That photo is at the intersection of Hwy 89 & Hwy 50 at about 19 hours. I get very emotional every time I see that photo.” – Al Arnold

Hello ULTRAS of the world. Yes, it’s me again. 🙂 And, as long as I’m still here I will, on occasion, give my “two cents worth.” So, dear participants of Badwater 135 2012, I’m sharing the final six week training schedule for my 1977 200 mile Death Valley (and all points in between) – Mt Whitney Summit “adventure”. Remember, I had no scientific data to benefit my preparations. I was a single “Research Lab” while on the run. But… it worked! My “old stuff” applies equally, today. I hope that you benefit from my past.

My final comment: Stay within your limits, avoid the hype … there shouldn’t be ANY DNF’s!!!!!

Good luck to you all.

The biggest challenge for endurance athletes isn’t the competition—it’s sun exposure, according to the latest Sun & Skin News, a publication of The Skin Cancer Foundation.

Triathletes, for example, compete outdoors in three endurance sports back-to-back—swimming, bicycling, and running. If racers don’t carefully protect themselves, notes Scott B. Phillips, MD, the result could be premature skin aging and skin cancers, including melanomas.

About half of the triathletes recently surveyed by Dr. Phillips had skin problems, and 55 percent of those with problems reported sunburns – almost the same results obtained from 259 marathoners.

“One problem for endurance athletes is that they wear less clothing in races than they do in workouts, exposing more sin to the sun,” says Dr. Phillips, in the Department of Dermatology at the St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Chicago, IL. “But the greatest about of exposure occurs during training, since athletes may work out several hours daily.”

Experienced competitors, however, learn many methods to avoid such threats. These strategies are advised for anyone exercising in the sun:

“These few moments make a big difference in sun safety, and little difference in your competitiveness,” says Dr. Phillips.

The Skin Cancer Foundation, the only national and international organization concerned solely with cancers of the skin, conducts public and medical education programs and provides support for research and professional training to reduce the incidence, morbidity, and mortality of skin cancers. Sun & Skin News, a quarterly publication of the Foundation, provides information on a broad range of topics related to skin health, including prevention and treatment of skin cancers, the effectiveness of new sunscreen formulas and sunglasses, prevention and treatment of photoaging, and the danger of tanning parlors.

For additional information, contact:

The Skin Cancer Foundation

245 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1403

New York, NY 10016

Hello all you crazy people:) I wish I were running with you. But, as Chris knows, I’m too old and toooooooooo slow!! Simply put: I miss being able to disappear into the shadows of solitude which graced the landscapes that engulfed my legs. They sure wandered during those endless miles of long slow trekking: mind and body, as one. But, always focused on “Death Valley Days” – a very powerful motivation that loomed significantly in the abyss of my mind and eventually to Badwater.

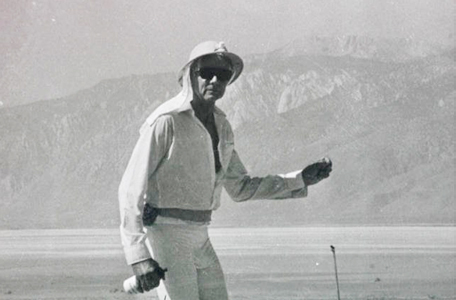

Twice I failed! In 1974 I almost killed my running partner, Dave Gabor. He collapsed at Furnace Creek. I continued on to ‘The Oasis’ when I stopped. I couldn’t stop worrying about his safety. I lost my focus. It was over. It took him a year to recover. By the way, the temperature at Stovepipe Wells was 121 F – AT MIDNIGHT! The mid-70’s were drought years. Just perfect to challenge the desert at its worst. Yes, I’m still alive:) David’s collapse was because of an intolerance to heat. I failed because I couldn’t stay focused. My second attempt was in 1975. Everything was fine until Towne Pass, at which point my left knee would not support downhill running. On my way to Stovepipe Wells I had gotten cute and tried running across Devil’s Golf Course. The crust couldn’t support my 225 pounds and so I hyper-extended my left knee. Again, I lost focus.

So my friends, old and new: Stay focused AND within your God-given capacity. There will always be “the back-of-the-pack.” There is no shame in that. You’re here because your guru, Chris Kostman, has decided to see just how tough you are. The new cut-off time of 48 hours tells me that Chris will expect only a stellar performance from each of you. Considering that, every team-participant has been a part of each runner’s total effort with the over-all logistics of the training/financial process. With this commitment behind you, then it’s time for NO DNF’s:) The formula, for all this is very simple: exercise PRUDENCE and don’t lose focus. 🙂

This “Adventure” into the bowels of Death Valley and beyond has many strange love attractions. So, as Cole Porter wrote, in 1929: “What Is This Thing Called Love?” The Badwater Ultramarathon is our alluring “love affair.” It has no competition. Each year we are drawn from all corners of our ever-changing world, for one purpose: competing in the World’s Toughest Foot Race. That being the case: Why is it so difficult to participate without any DNF’s? Each Ultra Athlete accepted into the race was required to submitted their “Ultra History” and yet the personal carnage still exists. Failure to follow common sense, while being swept up in the hype of the event, results in poor judgment of focus. This is no picnic: people die in the desert!!! The forty-eight hour cut-off is in line with he purpose of this year’s Badwater Ultramarathon. Serious Ultra competitors have progressed their athleticism, from the “Covered Wagon” to the levels of unimaginable performances: The Boston Marathon’s almost sub two hours, Badwater 135 with multi sub-24 hour finishs AND, Ten-Time Badwater finishers. It’s almost too fantastic to believe. Yet, in spite of the advance of training and sheer mind-power, failure still exists. This year’s Badwater will have the higher race demands than in previous events. So, why would you wish to quit? Do you train to fail, or is it that you have forgotten the power of being focused on the reason why you’re here? The excitement and emotion of the fanfare of the race can work for, as well as against, you. So, my fellow Ultras, please set reasonable and achievable goals while you’re on the course. Pre-race strategies are too often forgotten, especially so, once the action begins. And, of course, there will always be those amazing ten-time finishers who will make it look so smooth and easy. What can I say?

Here’s quote from one of the world’s greatest scientists and humanitarians: “Impossible missions are usually those that succeed.” -Jacques Cousteau

Have a great Adventure!

During the last twenty years of competing as an ultra runner I have heard countless stories about the famous Badwater Ultramarathon, the 135-mile running race held annually in July from Death Valley to Mt. Whitney. Since I don’t really like the heat, I have never desired to enter. However, so many runners are passionate about this race across Death Valley, their stories were intriguing, and I was curious.

When my coaching client Doug Ratliff informed me that he had been accepted into Badwater and wanted me to pace and crew for him, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to see what this race was all about.

First I began reading about how people acclimate for the race: Running in a sauna, cycling in a greenhouse, jogging on a treadmill with the clothes dryer vent blowing on you. While Doug didn’t do this, he did run in the Texas heat while we (his crew) practiced pacing and crewing. It was unlike any crewing experience I had ever had. I wondered “What could a runner need every half mile?” I was used to doing Mountain Ultras where I saw my crew every 2-3 hours, not every few minutes.

I got my first dose of Badwater reality when I arrived in Furnace Creek two days before the race. When I stepped out of the van, it was like jumping into an oven. The ambient temperature was 120, the wind was hot, and the sun was literally burning my skin. “How was Doug going to run in this, and boy am I glad I’m not,” were my first thoughts. I was beginning to understand the need for nearly constant crewing.

Almost immediately we began meeting other racers and crews. It was like any other ultra in that way, with friendly runners and helpful people. But there was more than that: many of these runners had completed multiple Badwater races, were back for more, and had only great things to say about the race. Bottom-line, I had never seen a group of runners, crews, and pacers so passionate about a race.

This was one of the only races I have attended where the crew consisted of more world-class runners than the race field itself. The crews were literally a who’s who of the running elite: Deena Kastor, Jenn Shelton, and scores of Badwater veterans.

There were a lot of rules! Support vans had to be tagged with the runner’s name and number. Crews had to adhere to race and traffic rules. The logistics involved seemed overwhelming.

As the race got underway I saw the need for all the rules. The 80 racers and some 400 crew members traveled across Death Valley like a well choreographed dance. Everyone worked together, runners and crew helping each other.

Just after the race began a woman approached me yelling, “Hey Hammer Girl.” (I was wearing my Hammer Nutrition shirt.) It seemed her runner had forgotten his HEED and was wondering if I had any. Our crew van was with Doug and I wasn’t sure if we had any HEED to spare. Fortunately we had an extra container so when our crew shift started, we tracked down the needy runner and delivered the HEED to his very appreciative crew.

Pacing Doug was much like pacing at any other ultra, except I had to stay behind, not in front of, him. My job was to keep him moving forward, limiting stops and distractions, while monitoring fluid and fuel intake. We dealt with the usual sleepiness, nausea, and sore feet. There were times that Doug wanted to sit or rest, so I began timing his stops and only allowing him 5 minutes. I kept him motivated by asking him about topics that he enjoyed talking about. Another tactic that worked was asking him to “run to the next marker.” The reality is that Doug had a great race and was a joy to pace and crew, even when the temps reached 110 during my 8-hour pacing shift.

Keeping the runner cool was something very new to me. I have been hot enough in races to drop some ice cubes into my hat and jog bra, but Badwater takes cooling to a whole new level. Our van was stocked with four huge coolers. The “refrigerator” was for those food and drinks which need to stay cool, but were not used frequently. One “coffin” cooler was used just to store about 20 bags of ice. The other coffin cooler was full of drinks, water bottles, plus ice and water to be used for keeping Doug cool. The last was a 7-gallon drink cooler full of ice and water. This cooler was kept sanitary and only an ice scoop was used to put ice in his water bottles, so that no bacteria would get into his drinking water.

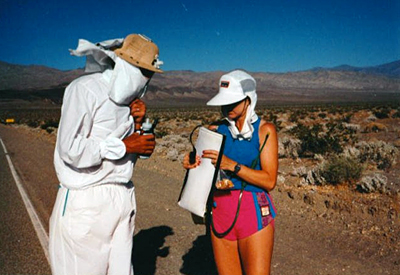

Doug used various methods to stay cool. The Moeben hemp wrap was soaked in ice water and worn around his head and shoulders (these were given to each race entrant). He also used the ice bandanas (specially made bandanas that can be filled with ice and tied around the neck), and water spays (industrial or garden sprayers filled with ice water that the crew used to mist him as he passed). All these measures seemed to work well as he never complained about the heat.

Besides the coolers, which took up the majority of the van, we had a tall chest of drawers with everything Doug might need: medical supplies, sunscreen, medications (anti-gas, anti-inflammatory , anti-nausea, etc), Endurolytes, sports lube, powder, foot kit, batteries, lights, etc. There was also a chair and a large umbrella; we had to hide Doug with the umbrella when he needed to change clothes or urinate (there are no bushes to duck behind). We also had two-way radios so the pacer could inform the crew of anything Doug needed before we passed the van again.

We also had a notebook in the van with all of the crew information and a spot to record all of Doug’s intake and output (as well as anything else we thought interesting or pertinent). It was nice to be able to look at this and realize that Doug needed something. He typically drank about 20-24 oz of water and took three Endurolytes per hour. He supplemented HEED with various drinks and food throughout the race.

Overall, I was most impressed with all of the organization. Doug had assembled a first class crew, provided us with all of the information we needed to help him, be where we needed to be, and take care of ourselves. Doug’s race was terrific, there were no horror stories, no giant blisters, no endless vomiting. He was even running up the 13 miles to to the Whitney Portal finish line!

Of course the finish line of any event is the highlight and this was no different. Doug crossed the line with all six of us in tow, was greeted by Chris Kostman, the race director, and presented with his buckle, medal, and coveted finisher’s shirt.

The race experience wasn’t over yet: The post-race awards and party was more of the same: camaraderie, appreciation, and friendship. Runners and crew assembled to applaud the efforts of each one out there. The race recap video was touching! But a couple of amazing things stand out about the results: First, only 7 runners DNF’d. This is one of the most brutal events in the world and yet a huge majority of these runners battle the crazy conditions and make it to the finish line. Second, many of them were finishing more that once, some up to 15 times. Veteran crew members were also recognized, with two women having crewed ten times each!

When Doug had first approached me about coaching him to get to Badwater, my response was, “I’m happy to work with you through the qualifying events but I am not comfortable coaching you for Badwater itself.” I knew Badwater is a special kind of race with a set of circumstances (namely heat) with which I had never dealt before. So, I worked with Doug on his qualifying 100-mile races. For training, he did up to 100 miles per week but was not consistent with his running until he started a running group in San Antonio. The group forced him to be consistent because he was expected to show up for runs.

Because he had crewed at Badwater several times he knew what it would take to finish. He was very organized and had every aspect of his race preplanned, but also had alternate plans in case things did not go well. Another aspect of Doug’s success was intense training in the Texas heat with the van and crew just as it would be during the race. This enabled everyone to experience what we would be up against. Doug tested everything from race fuel to clothing, shoes, and more. He even figured out which shoes he could wear, and when, based on how quickly they dried. Lastly, Doug’s participation in a 48-hour event really helped boost his confidence and gave him a taste of how it would feel to be on his feet for that length of time. All of this added up to a great experience for him and his crew. Each of us was ready to take on the Badwater task and Doug had a “picture perfect race” as crewmember Brenda Carawan put it.

We all spent two days in Las Vegas after the race, lounging and eating (a lot). Doug drove back to San Antonio and began doing short runs the next week. He says the most difficult part of recovery has been sleepiness and being tired. It took him the better part of two weeks to get caught up on rest. His next race is the Arkansas Traveler 100 in October.

While I still contend that this is not a race for me (I have learned “never say never”), I now understand the allure of Badwater. I understand that this group of runners is somehow connected and part of a very special corps of athletes who have not only overcome, but embraced, the climate and adversity of Death Valley.

Amanda McIntosh with Badwater 135 Ultramarathon race director Chris Kostman at the 2010 finish line

Coach Amanda McIntosh has been a Hammer Nutrition Athlete since 1995. Some of her racing highlights include 1999 50 mile National Women’s Champion, 1999 and 2000 Leadville Trail 100 Women’s Champion, 2005 World Masters 100K Women’s Champion, 2008 Copper Canyon 50-mile Women’s Champion, 2007 Q50 Patagonia Women’s Champion, and 2010 Q50 Costa Rica Women’s Champion. Over the past year Amanda has added cycling and swimming to her running, competing in a few Triathlon and Duathlon events. As a coach she trains beginner to elite runners to accomplish goals from 5k to 100 miles and more. Though Amanda is based in San Antonio, TX, her clients include athletes from all over the world. She thinks Chris Kostman is Da Bomb.

By Chris Kostman

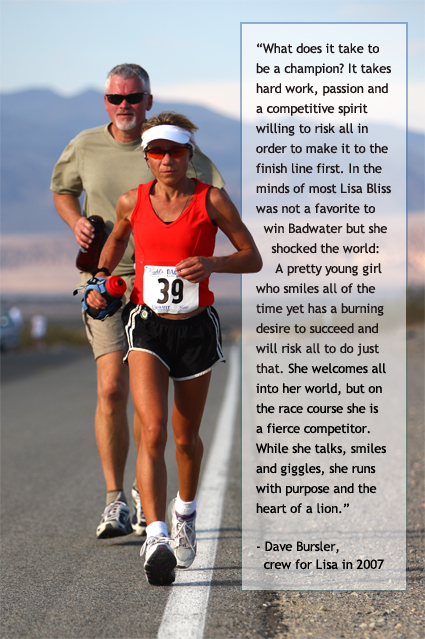

If any one person has “seen it all,” literally, at the world’s toughest foot race, it’s Dr. Lisa Bliss of Spokane, WA. It all began in 2002 when she served on the support crew for Steven Silver. He notched his sixth and final finish that year, but Lisa’s long love affair with Death Valley, Mt. Whitney, and the Badwater Family had only just begun.

If any one person has “seen it all,” literally, at the world’s toughest foot race, it’s Dr. Lisa Bliss of Spokane, WA. It all began in 2002 when she served on the support crew for Steven Silver. He notched his sixth and final finish that year, but Lisa’s long love affair with Death Valley, Mt. Whitney, and the Badwater Family had only just begun.

In 2003 Lisa returned to head up the race’s first ever Medical Team, an important step in the evolution of, and focus on safety and professionalism for, the 135-mile foot race held in the world’s most inhospitable environment.

In 2004 she organized the Medical Team before the race, then toed the starting line as competitor. She placed 3rd woman and 15th overall in her rookie debut, with an impressive time of 37:41:48.

In 2005 she returned as Medical Director, while also heading up the “Study on Fluids and Electrolyte Balance: Hyponatremia in Ultramarathoners,” enlarging on her career in the science of ultra sports, something which would lead her to presenting several years’ worth of research findings and making her an in-demand speaker at sport science conferences.

In 2006, Lisa once again organized and directed the Medical Team, and also conducted more research on the athletes, this time a “Sodium Balance Study,” which, among other things discovered that “those who reported the most heat acclimatization training prior to the race had a lower sweat sodium concentration at the start,” and “sodium balance homeostasis was maintained despite extraordinarily challenging conditions and bodily stress.”

Entering 2007, Lisa had crewed once, competed once, directed the medical team for three years, and conducted two years of scientific research at the race. Having seen and done and learned so much at Badwater, literally nobody knew what she knew about surviving, and succeeding, at Badwater. It was time to get back in the arena as a competitor and put all that knowledge and wisdom to good use!

The 2007 race was never easy for Lisa; she had to stop twice to tend to major blisters, and she battled through a variety of challenges. But, aided by a crew of close friends, she pressed on, racing towards her own vision of her highest self. At mile 72 at Panamint Springs, she was three hours, 25 minutes behind the women’s race leader, a rookie fireball named Jamie Donaldson.

As the miles and hours passed, Lisa discovered that she was getting stronger and stronger. On Towne Pass she had been the fifth woman, but from there on she started passing her rivals one by one all the way to Lone Pine where she finally caught the now ailing Jamie Donaldson.

“Maybe they just went out a little too hard. Maybe I benefited from all those long stops I was taking to tend to my blisters and tendon problem. I don’t know, but at around 90 miles I started to feel real good and just began running. I must have had the fastest woman’s split form Darwin to Lone Pine. I ran the whole way,” said Bliss after the finish.

Bliss passed Donaldson at Lone Pine, 122 miles into the race with only 13 miles remaining, and went on to win with a time of 34:33:40. Everybody was happy for Lisa, even the competitors she’d passed on the way into Lone Pine and on the way to Whitney Portal.

Never one to bask in glory, or to try to “defend a title,” Lisa returned to Badwater in 2008 and 2009 to again head up what had become, with her direction and inspiration, the finest Medical Team at any ultra event. That same Medical Team from 2009 is back in 2010, with one new addition, proof that Lisa is a great leader who brings out the best in people who want to work with and for her.

Over nine years, Lisa poked and prodded ill-stricken racers (and crew members and even race sponsors), who, more often than not, were able to complete their races after receiving care from Lisa and her team. She saw athletes at their worst, she took care of them with an ever-present smile, she observed, she learned, she listened, she put her food down whenever necessary, and she has done her best, always, to help the Badwater Ultramarathon remain a safe and respected race. For that, and so much more, we are thankful.

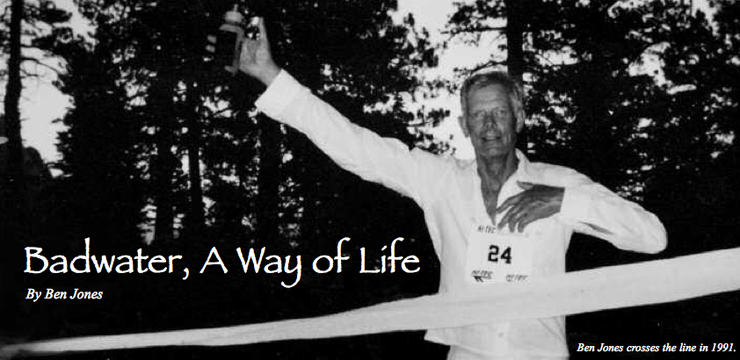

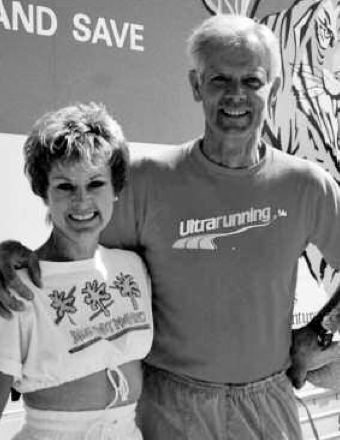

Ben and Denise Jones Inducted into the Badwater Ultramarathon Hall of Fame

In recognition of their 17 years on the race course as athletes, camp hosts, volunteers, crew members, race ambassadors, and Mayor and First Lady, Ben and Denise Jones were inducted into the Badwater Ultramarathon Hall of Fame in July, 2007. Both of them are three-time official finishers, as well as training camp hosts and mentors to many Badwater runners.

Denise has crewed Ben three times (1991, 1992, and 1993). On crewing her husband Denise says, “He is delightful to crew, one of the best-natured people on the planet. Never complains and is always kind and it was always fun!!!”

Her crewing resumé for other Badwater crossings and desert crossings is as follows:

|

Their plaque reads: Badwater Hall of Fame Ben and Denise Jones |

Audio interview with |

Ben is an avid photographer of Death Valley, the Eastern Sierras,

and various ultrarunning and ultracycling events.

Click here to check out his many great photos!

My introduction to Death Valley was in talking to several great aunts who first went to Death Valley in the ’20’s via a Los Angeles-to-Baker train line. Along the way were the Harvey Houses. Then there was the Tonopah-Tidewater Line to Death Valley Junction. From there a spur-line took them to Ryan and then a coach to Greenwater (Furnace Creek). They used to tell me of the adventure which took about a week each way in those days.

My folks first took me to Death Valley in the late ’30’s. There is a picture of me at Mushroom Rock (which appeared larger then). In 1963, I moved to Lone Pine (mile 122 on the race course) to practice medicine, where I have been ever since. In 1965, I was offered office space across from Furnace Creek Inn. I went there on my “days off’ during the Harvey Company’s tourist season (October to May) for over twenty five years. At the time I had an airplane (Cessna 205) making the trip easier and more fun. During those years, after seeing patients at the clinic, I would train in and around the area.

In the decade from 1977 to 1987, I had (later) heard that there were about 10 individuals (with documented records) who did a solo crossing from Badwater to the top of Whitney (146 miles) as well as about ten others who are on record. About this time, Hi-Tec Sports USA created a race on the Badwater to Mt. Whitney route in order to promote the “Badwater 146” running shoe. In 1989, seven finished.

In 1990, there were seventeen finishers and I knew two runners who had been “invited.” I went out on the course to try to find them but couldn’t as they were doing the “bed and breakfast” version. The first runner I saw was “Marshall.” and, at the time, I thought that was his last name. Later I met other faster frontrunners, followed by those runners “reduced to walking.” My thoughts were, if I just walked, I could do it also.

In 1991, I asked to be “invited” and was accepted about three weeks before the event. Over the Fourth of July Holiday, I was “walking” along near Keeler when a vehicle pulled over to see what was happening. It turned out to be Tom Crawford, Rich Benyo, Rhonda Provost, and Drew Benyo on their way to their annual training camp at Panamint Springs Resort. I was already familiar with their article, “From Fire to Ice to Fire” in UltraRunning Magazine and Richard’s book, “Death Valley 300.” I asked to be “invited” to train with them so, on the next day; we did a practice run from Badwater to Furnace Creek. (Editor’s note: Crawford, R. Benyo, and Provost are all Badwater Ultramarathon Hall of Fame members.)

Later, after my first successful “race” in 1991 they were even more impressed that I had taken time out during the race to do an autopsy. It was on a fallen trekker who was not successful in navigating the saltpan of Lake Manley (Death Valley). They also liked the idea that one of my cooling devices was a water-filled casket in a U-Haul truck. These happenings lead to the concept of “Mayor” and “First Lady” of Badwater. After that I had two more successful crossings, in 1992 and 1993. My wife, Denise, also subsequently had three successful crossings, in 1994, 1996, and 1999.

Denise and I got married in 1990. In the early ’90’s, we began to bump into other runners training for Badwater. We began organizing heat-training clinics to help the athletes prepare for the races. We held them on Memorial weekend and Fourth of July weekend each year. Over the years we got to really know the folks who attended and their crew members, pacers, family members, as well as some interesting newbies and wannabes. It made it much more interesting and fun when the race finally happened each year. We were able to provide useful information about replacement of fluids, electrolytes and calories as well as heat adaptation. This has translated into a success rate of about 85% for the attendees. In addition, we have crewed (and paced) runners during some of the races as well as some on their own solo adventures.

Denise and I were in the 1994 race as the “Mayor” and “First Lady” of Badater. She was successful in getting to the Portals and to the top of Whitney. I had renal failure and dropped at 41 miles. We both entered in 1996, but as two separate teams. Again, she was successful in making it to the Portals. A storm kept her from making the top that year. I dropped due to exhaustion from overwork and issues of depression (not race related). She was again successful in 1999.

1999 was a big year for media coverage. Kirk Johnson, sports editor for the New York Times, came to our clinic and did the race that year. Following his performance he wrote a book entitled “To the Edge.” Also, “Running on the Sun” was directed by Mel Stuart and produced by Leland Hammerschmitt in 1999. Kirk Johnson, Marshall Ulrich, Lisa Smith, and many others are featured in this production, along with me.

Ben and Denise Jons

Ben and Denise JonsI turned 70 at the end of 2002 and decided to try it as the first ever 70-year old in 2003. This time I suffered from the 139 degree temperatures and my own 101 degree internal temperature. I decided, being the only one on call for the Inyo and Mono Coroner’s Offices that I didn’t want to have to do an autopsy on myself. Besides that, I was having hallucinations about being in the Garden of Eden and seeing Mary Magdalene as well as being wrapped in a shroud (of Turin).

Other athletic experiences in the area have included the annual Death Valley-Whitney bike race, which I did eight times in a row. In 1991, I ran the first Titus Canyon/Death Valley Marathon (and the four after that). Actually, I had practiced on that course on my own before that.

Our further involvement in Death Valley included supporting the following: (1) Marshall Ulrich’s South-to-North Crossing of Death Valley National Monument; (2) Marshall’s Death Valley Solo, Unsupported Crossing (we were present with the camera); (3) Scott Weber in his Oasis-to-Oasis Triple/Quad; (4) Denise helped Rhonda Provost by pacing her up and down Mt. Whitney as the first woman to do the Double Crossing in 1995; (5) Denise crewed Shannon Farar-Griefer as the first woman to do the Double Crossing within the race context; (6) Denise crewed for Adam Bookspan in the South-to-North Crossing in 2002; (7) Denise crewed for Lisa Smith-Batchen with Double Crossing in 2006. 8) Last summer, I had the pleasure of helping Scott Jurek, along with his wife, Leah, with a day of desert training as well as filming his workout performance. I then crewed for Pam Reed during the 2006 race.

Denise has crewed for the race and in solo crossings a total of 15 times, which includes 3 double crossings. This led to her to join with Theresa Daus-Weber in writing a book about crewing. “Death Valley Ultras: The Complete Crewing Guide” was published in May 2006. It is a technical guide with a comprehensive collection of information to plan and crew a successful Death Valley ultra with instructions, tips, a list of the known Death Valley crossings, and a photo gallery of views from the Badwater Ultramarathon course.

There were two nice publications during 2006. The first was an article featuring me in Best Life (Men’s Health), by Rodale Publications in the March 2006 issue. The title of the article is, “A Prescription for Lifelong Health.” A photographer visited me and took 20 rolls of 12 shots each with his Hasselblad camera using IMAX film; one was used in the article. Then I was interviewed by the executive editor for three hours for the two-page article. The second was a DVD produced by PBS/Nature entitled, “Life in Death Valley.” While they were there on a half-dozen trips, not only did they film the wildlife, but they were also involved in flash floods, a once-in-a-lifetime wildflower display, and the Badwater Ultramarathon. I was pleased to be a part of the feature.

All in all, we have seen this Race from a complete perspective: participant, camp host, volunteer, crew member, “Race Ambassadors,” as well as “Mayor” and “First Lady.”

Badwater/Whitney has become a way of life for us. Doing the race is not necessarily “good for the body,” but is offset by being good for the mind, soul, and spirit. The concept of adventure racing and extreme sports is here to stay. We enjoy keeping up with our friends and meeting more people who share the same types of adventures.